“Public health refers to all organized measures (whether public or private) to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among the population as a whole.” - World Health Organization

“Public health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals.” - Charles Edward Amory Winslow.

We asked a few Loma Linda University schools and people in the San Bernardino community to write about public health using the definitions above as a guide. The question we posed? How do you see your profession impacting the lives of people in the surrounding communities, especially those in the city of San Bernardino?

Click the names below to read their responses.

Dr. Handysides is the director for the MPH Health Education program and an associate professor in the School of Public Health [dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is often said that we must practice what we preach. But what does this mean in the world of public health? This question has been circulating in my mind for a number of months now. At Loma Linda University School of Public Health, we have a rich history of professors that set a distinct example of doing just this. In the corridors of Nichol Hall, students interact with faculty and staff who are often deeply engaged in both the role of a classroom education and the essential tangible role of practice within the community. So what does public health practice look like? Depending on the disciple within the profession it can be vastly different. As I watch epidemiologist Dr. John Morgan skillfully examine and explore the data surrounding cancer, I see a practitioner at his best. His research leads to insight into possible interventions and highlights previously unknown risk factors. But he does not stop at the research; he actively shares his results with health care officials and policy makers to improve the day to day workings of public health practitioners in the field. I can move further through the building and see a person like Dr. Juan Carlos Belliard, who spends considerable time fostering and strengthening our connections with local non-government organizations and community members. His work has continued to reach out to those around us, and keep us active as a school in both the local and global fight for better public health. There is a wide variety of practice that takes place, and all of it needs to be enhanced and promoted. One of the first items to remember is that we as a school are not striving for uniformity of practice but rather unity. Our goal is to implement the mission of the university, “To make man whole” with the motto and methods of our profession. As a nation we are struggling with non-communicable disease; obesity is continuing to grow and spread across the population. Alcohol, tobacco, and drugs continue to rob youth of a vibrant future. Social, racial, and economic equity continue to be issues that need to be addressed. The issues are vast. This issue presents the needs for collaboration and partnership as never before. As a school of public health we must come together to face these challenges, no one can be a “teacher” or “researcher” or even a “practitioner” alone. Gone are the times when disciplines could function with relative success in silos. The modern world and its growing list of threats to health demand a collaborative approach, where research is translational, where didactics are infused with practice, and where partnership is sought with as much vigor as publication. Our alumni, the surrounding community and our students look forward to being partners in this change. We have been good in the past. This is not a call to start something novel. This is a call to enhance, to put fresh hands to the plow, to recommit to the calling that is uniquely ours. We as Loma Linda University School of Public Health have been placed here for a purpose. It’s our time to make a difference. John McMahon was appointed Sheriff-Coroner of San Bernardino County by the Board of Supervisors on December 31, 2012.

Homelessness is an extremely complex social issue that affects the quality of life throughout San Bernardino County, and one which law enforcement is called upon to address daily. Our county has taken several steps to help people move beyond homelessness. As a law enforcement agency, our deputies generally respond to several daily calls for service involving transients. The traditional law enforcement approach to such calls has been to rely upon arrest and incarceration. This model has proven ineffective and involves a high rate of recidivism. This cycle of arrest and incarceration distances the homeless community from law enforcement and from accepting services. A joint response with public health strengthens the collaborative effort to better address the homeless problem in San Bernardino County. The non-traditional approach of the Homeless Outreach Proactive Enforcement (HOPE) program is to work with and connect the homeless population with services, while reducing recidivism and improving the quality of life for all county residents.

The HOPE program is an innovative approach to assist homeless individuals back into mainstream society. Working together with service providers, faith based organizations, and other community groups is the only effective way to successfully reduce homelessness. Since its inception, the HOPE program has many success stories involving homeless individuals. The Sheriff’s Department is excited to partner with the Loma Linda University School of Public Health to address the needs of the homeless population and our communities.

Collaborating with LLU SPH to provide a better response to homelessness just makes sense. Homelessness is a key factor in one’s health and has been associated with an increased risk of physical illness, chronic disease and poor mental health, compared to the general public. The living conditions of the homeless population cause an array of health and medical issues due to lack of care and hygiene. Collaborating as an outreach team, the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department and the Loma Linda University School of Public Health can better address these issues and

seek to improve and maintain this homeless strategy.

The Sheriff’s Department is dedicated to partnering with organizations in the effort to assist the homeless with services from basic needs to housing. LLU SPH can provide numerous services to reduce homelessness. The LLU SPH is an innovative part of the solution, and can provide the homeless population throughout the county with services from addressing medical needs to ongoing support. Many homeless individuals have severe medical problems, but are reluctant or are unaware of where to seek medical attention.

Through collaboration, the HOPE program and the LLU SPH can provide services throughout the county. This partnership will allow students to learn more about the state of public health associated with the homeless population. Earlier detection, intervention, and treatment can improve the opportunity to diminish the risk of disease, not only to this high risk group, but to the community as a whole. I want to emphasize that collaboration can only strengthen the number and quality of services provided by both agencies, and it can serve as a model for other agencies to follow. The LLU SPH will be at the forefront of data collection in order to reach out to the homeless.

These non-traditional partnerships will lead the way in reducing homelessness while improving the quality of life in San Bernardino County. Linking these two influential departments will further the cause of homeless-related issues throughout the county, and better streamline the assistance process. The collaboration will lead the way as an effective approach to homelessness. As we work together we will be able to offer a more effective helping hand to the homeless population in San Bernardino County.

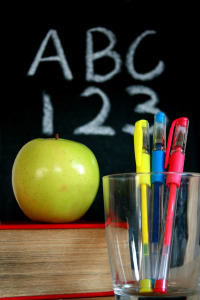

Jerry Almendarez has been the Superintendent for the Colton Joint Unified School District since 2010.

The Colton Joint Unified School District (CJUSD) is one of 38 school districts within the county of San Bernardino. The CJUSD includes the cities of Fontana, Rialto, Colton, San Bernardino, Bloomington, Grand Terrace and Loma Linda. Of the 412,000 students who attend school in San Bernardino County, approximately 22,692 of them are enrolled in the CJUSD.

On January 16, 2014, the State Board of Education approved regulations providing guidance to districts on Governor Jerry Brown’s historic education finance law. The law requires parents, students, teachers, and other community members to be involved in the process of deciding how dollars are spent. With the governor’s new funding formula comes a requirement for each district to draft a local control and accountability plan. This document starts with eight state priorities, they are as follows; student achievement, student engagement, school climate, basic services, implementation of common core standards, course access, parental involvement and other student outcomes. It then requires us to map how our efforts will support these priorities, and how we will direct funds accordingly.

In order to truly be ready for the future, education cannot act alone. The collaboration should extend beyond our classrooms and offices and into the broader community. Last year we formed our community cabinet, a diverse group of education, government, business and labor, community and faith-based organizations together with parents and staff. One of the relationships strengthened by the community cabinet is with Loma Linda University School of Public Health. This relationship will enhance both the MPH student experience and the outcomes of our students. Having MPH students and faculty interact with our schools, through practicum, research, service learning, after school programs, etcetera, will continue to improve our district.

It is so gratifying to see the level of interest and dedication from our business, non-profit, faith-based, and government partners. The more we build on this effort, the more our students will know we care about their success.

We are so fortunate in CJUSD to have a group of employees who are such caring professionals, a dedicated Board of Education and parents and community who are dedicated to our children’s future.

Dr. Marshak is an assistant professor in the LLU School of Allied Health Professions

Public health can be seen as both a general term encompassing all people wherever they live, and as a specialized term incorporating the traditional areas as defined by the profession in the US and elsewhere: environmental health, biostatistics, epidemiology, etc.

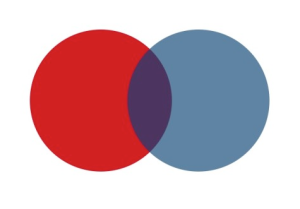

Where Allied Health differs from public health is in the focus of the practitioner. Whereas public health practitioners focus on the needs and problems of the population, society, or humanity globally, allied health practitioners focus on the specific needs of the individual. If you will: macro-health in contrast to custom-health. To accomplish this public health marshals the efforts of a group of individuals to accomplish what one individual could not. While all people benefit from the results of public health in practice (clean air, water, nutritious food, etc.), only those with a specific need benefit from the practice of allied health practitioners. Individuals with specific needs visit a physical therapist, or an occupational therapist. Only those with Asthma that requires hospitalization, or who suffer respiratory arrest are treated by Respiratory Therapists.

These two areas also overlap, like circles on a Venn diagram. You also cannot have one without the other. This was clearly indicated with Loma Linda University’s response to the Haiti earthquake disaster. SPH faculty, students, and graduates helped rebuild the infrastructure and provide clean water, waste disposal, and disease prevention. Concurrently Allied health faculty, students, and alumni were assisting the individual needs of those injured, maimed, and traumatized by the disastrous event.

Closer to home, faculty and students from the various departments in allied health collaborate with their colleagues in public health to assist the underserved in San Bernardino and Riverside counties. They work with providing shelters for battered women and the homeless extending the arms of their professions into the community.

So it is not entirely due to coincidence that the schools of public health and allied health professions share a building here at LLU. We also share the desire that drives us to the professions we choose, so that we can help our fellow man, wherever he or she may be, to the best of our abilities, while looking after our families and loved ones in the process. We practice what is so well articulated in our motto: TO MAKE MAN WHOLE.

Burt Clark is the Director of Outreach, UReach at Loma Linda University Church

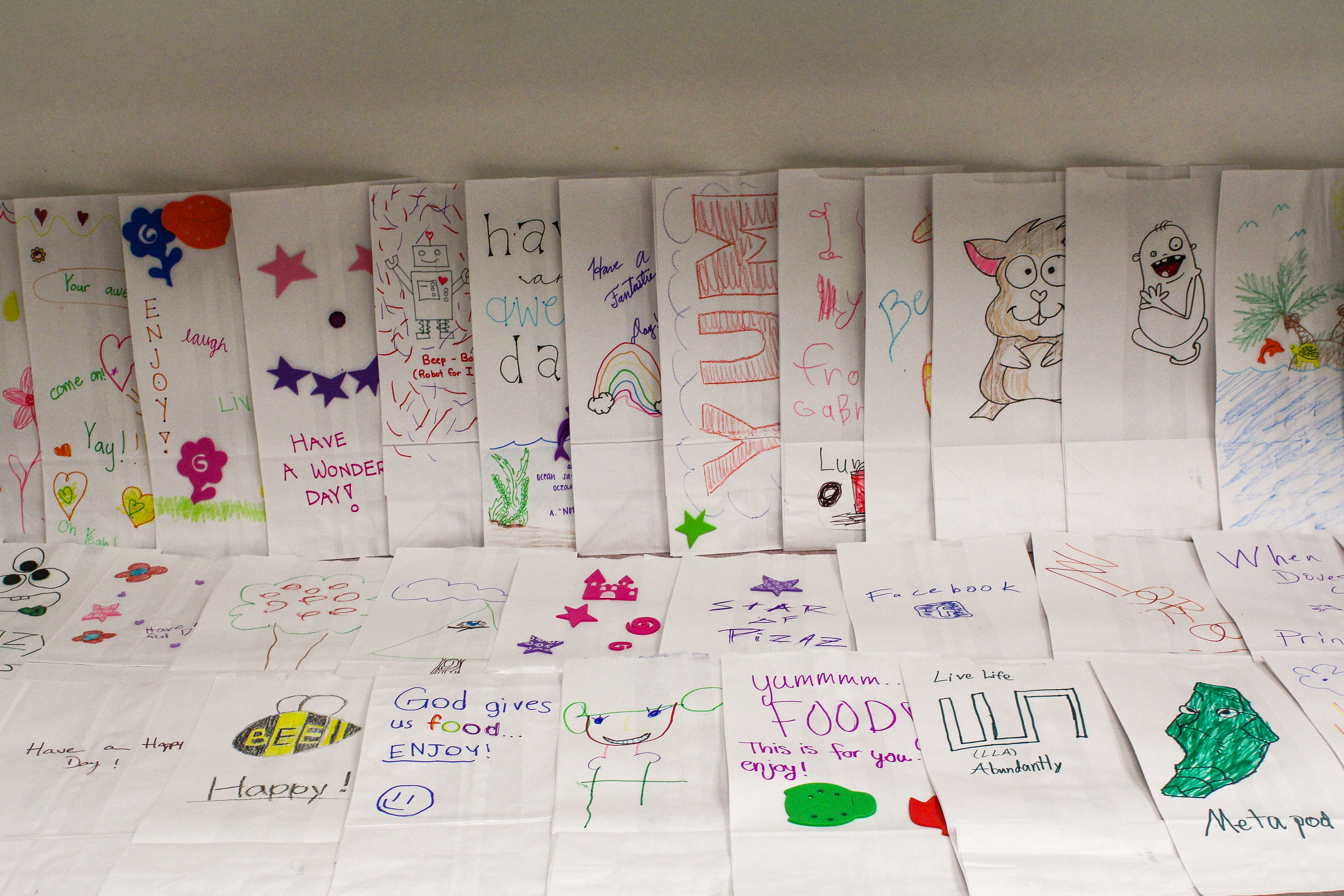

Many times within churches and non-profit organizations, a lack of collaboration exists. Within each organization is a sense that we have a good program, and if we work with others then we don’t have it all figured out. For example, a church may run a food pantry, and a clothing ministry, but so does the church that is a few blocks away. Both ministries serve the same group of people, and both do good work. Each church’s impact is limited by the funding that they have available. The church does as much as it possibly can.

The problem is that the individuals who are being served are never truly helped. They continue to muddle in their situation. They survive, and the church fulfills the mission of serving the community. For the individual, no real change has taken place. The person being helped will return the next week, and the next, until some thing in their life changes; which may never be.

So what can we be doing? As followers of Christ, and believers in following His call set out in Matthew 25, we must serve. But there could be another way. What we, as churches and non-profits, have been doing is working in silo’s. Each one of us does our own thing, even within denominations; many times we don’t work together. Even more than this, we don’t work with non-profits who may be doing the exact thing we are doing. Somehow we feel we will lose our church’s impact if we collaborate. But that says God is not big enough to work through us wherever He calls us.

The new model of outreach is that of collective impact. When we bring churches together to talk and collaborate, we can truly affect people and help them change their life. This is not an easy process, it is much harder than giving out food and clothing, but it allows for real community transformation. When we bring all of our resources to the table and say, how can we make more of an impact here and now, we can accomplish much more.

For UReach, the outreach ministry of the Loma Linda University Church, this has been something we have been working toward for some time. We sit on the same campus as Loma Linda University, and there are still programs that we run, in the same areas, and for the same people. But we are trying to expand this practice. One such collaboration is between UReach and the School of Public Health. This is a partnership that benefits both entities, and the people with whom they work.

When working to serve the communities, churches have certain barriers; they may have volunteers, but may lack the knowledge. There are also projects that need to be completed, but we cannot gain the necessary funding. The funds exist but because we cannot combine federal grant money, and funding from certain organizations it is impossible for the projects to move forward. The collaborative partnership that we have with LLU SPH bridges these gaps. Students can fill in where church members are not available, and church members can stay connected to the community when students leave for break.

The partnership also allows for both organizations to make connections in the community that would not otherwise have been possible. Both organizations are connected to the local community in different ways. LLU is connected through reputation, history, and programs that have been operated for community benefit. UReach is connected to other churches, and individuals who need guidance, as they become productive members of society. Both organizations have connections with community organizations that can benefit the collaboration, but would not be known without the partnership.

The bottom line is we need each other. We are stronger through our work together. UReach understands that collaboration is what can, and will make our organization stronger. As UReach and LLU SPH work together it is our desire that others will join with us as we collaborate to better the communities where we live.

Dr. Gillespie is an assistant professor in the school of public health and Faith Community and Health Liaison at Loma Linda University Health

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]ary Gunderson, the forerunner of the faith and health movement within the United States (leadingcausesoflife.blogspot.com), says this, “A movement isn’t a movement until it has a common idea.” This common idea of a placed-based collaborative (PBC) approach to faith, health and innovation came from a deeply held Adventist understanding that health ministry is part of the work that Jesus did while he was here on earth. The mission statement of Loma Linda University Health is to “continue the healing and teaching ministry of Jesus Christ.” And this PBC will continue this work with a deep appreciation for the place to which we have been called.

Place-ment

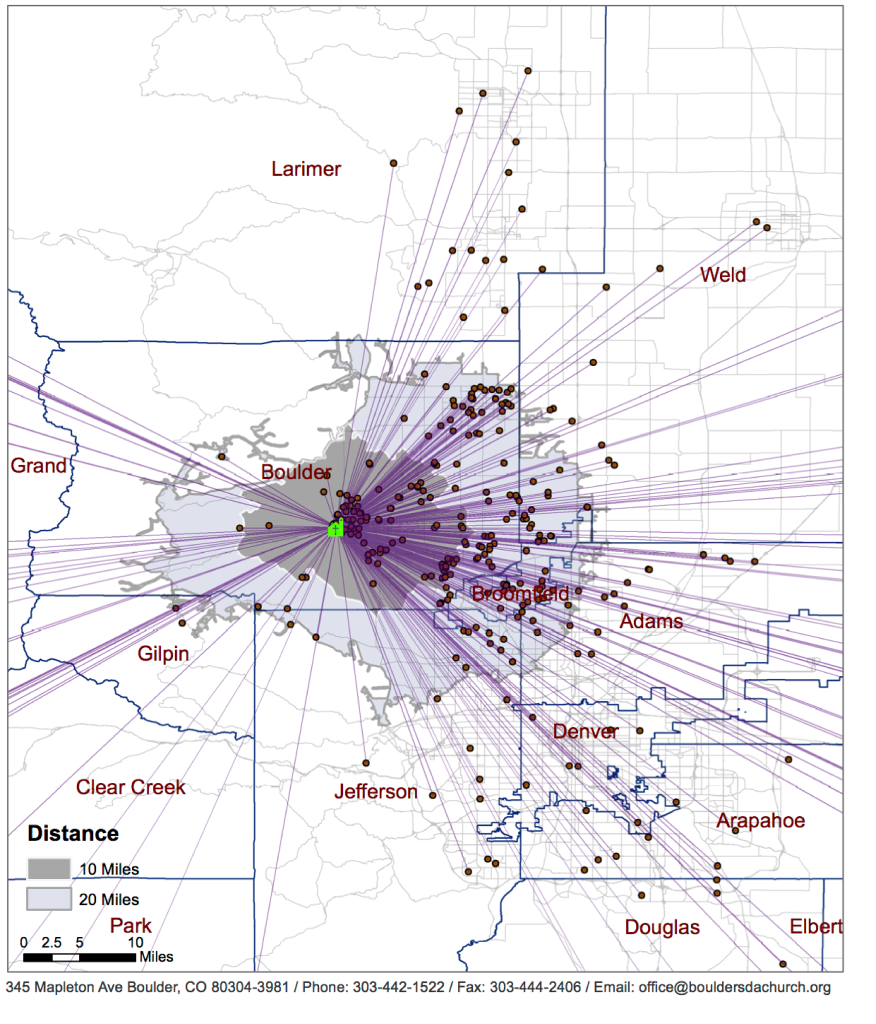

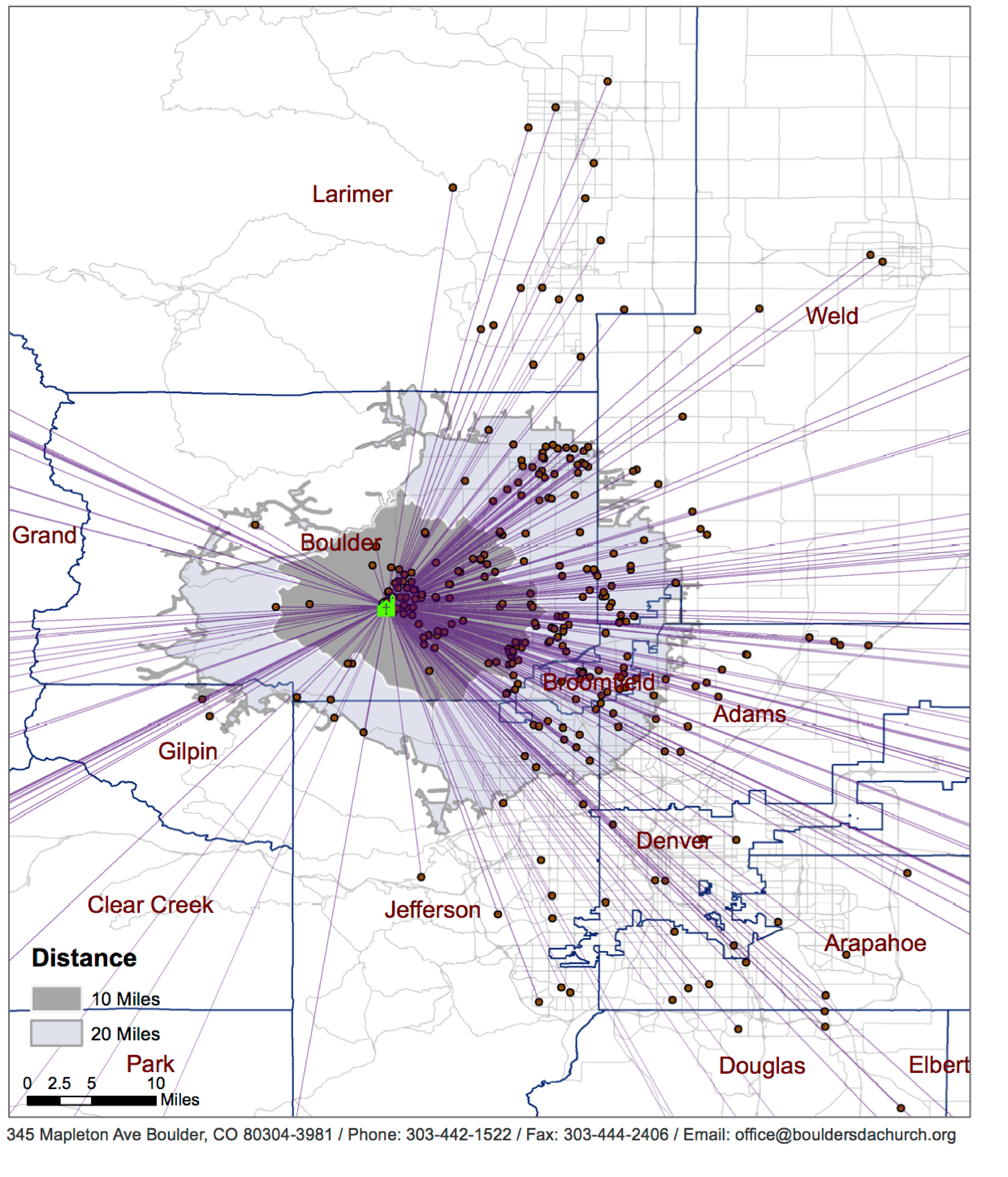

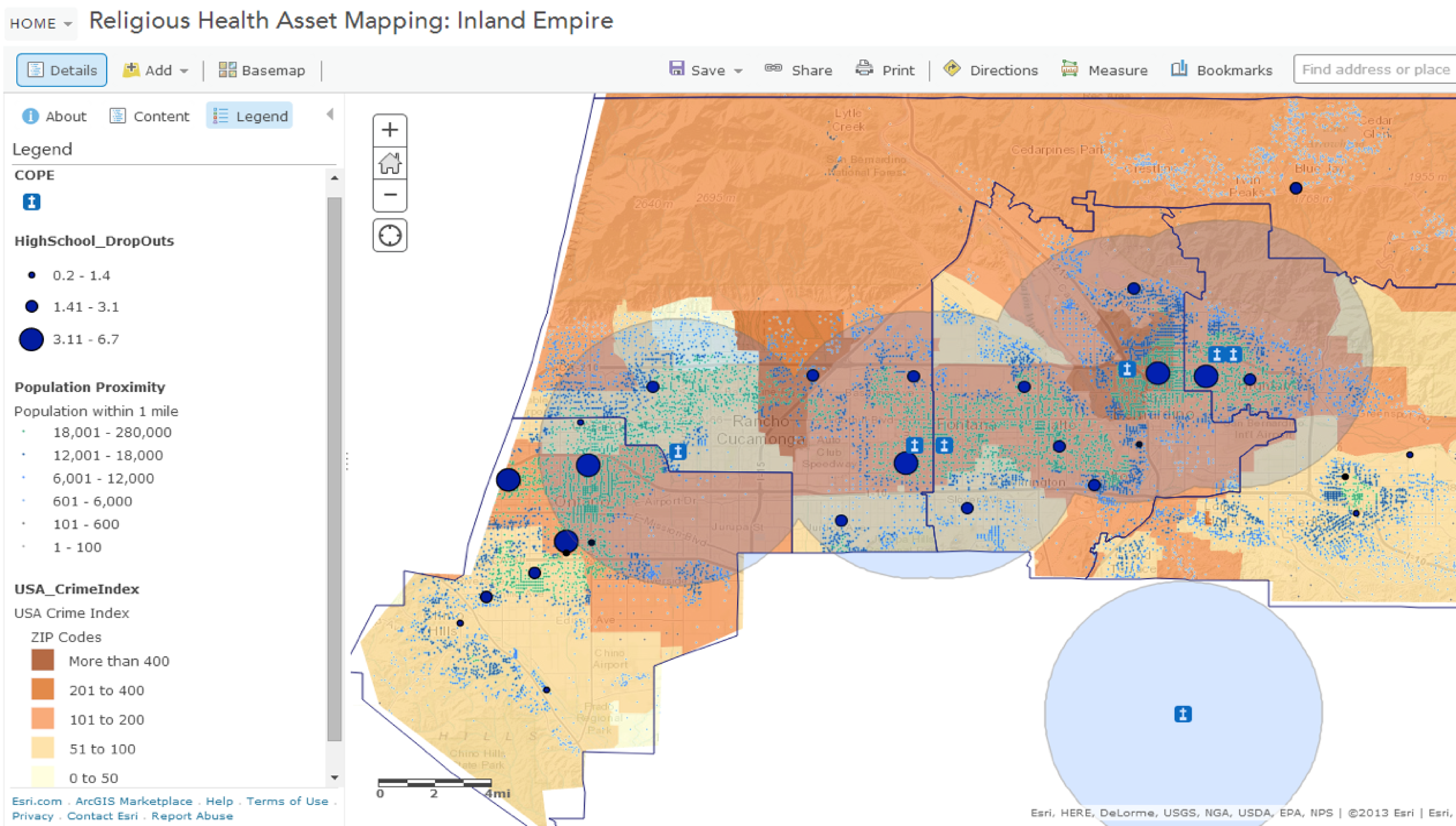

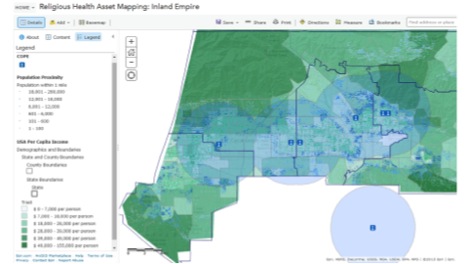

The importance of place should be quite obvious. Churches exist in geographic locations, and one would think that these churches exist to provide spiritual guidance, care, and compassion to those in these areas. However, this conversation is much more complex than would first seem. The complexity comes from a myriad of historical, social, economic, ecclesial, and cultural issues. Issues, which if not seen clearly, actually conspire to disconnect the worshipping body (congregation) from the place (church) they find themselves driving to in order to worship. (See Image 1–This is an image of a mapping of church membership for the Boulder Church, as you can see, the majority of it’s congregation is outside of a 10 mile radius, and many members are outside of a 20 mile radius from the church.)

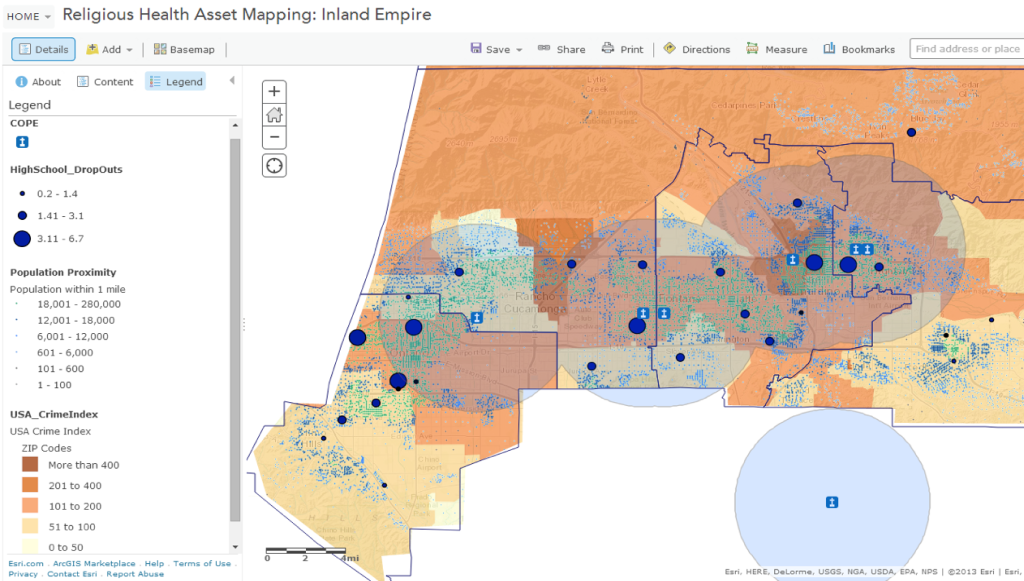

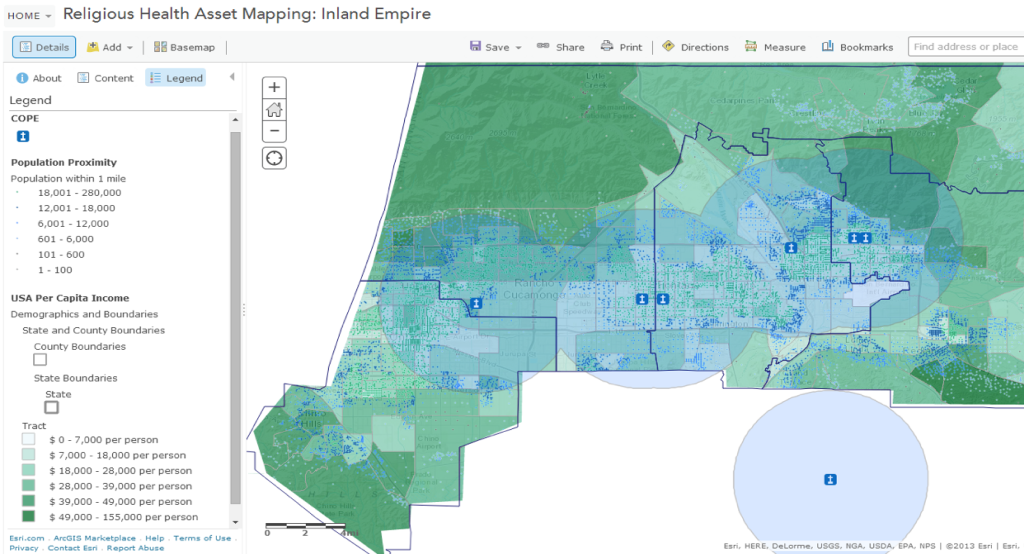

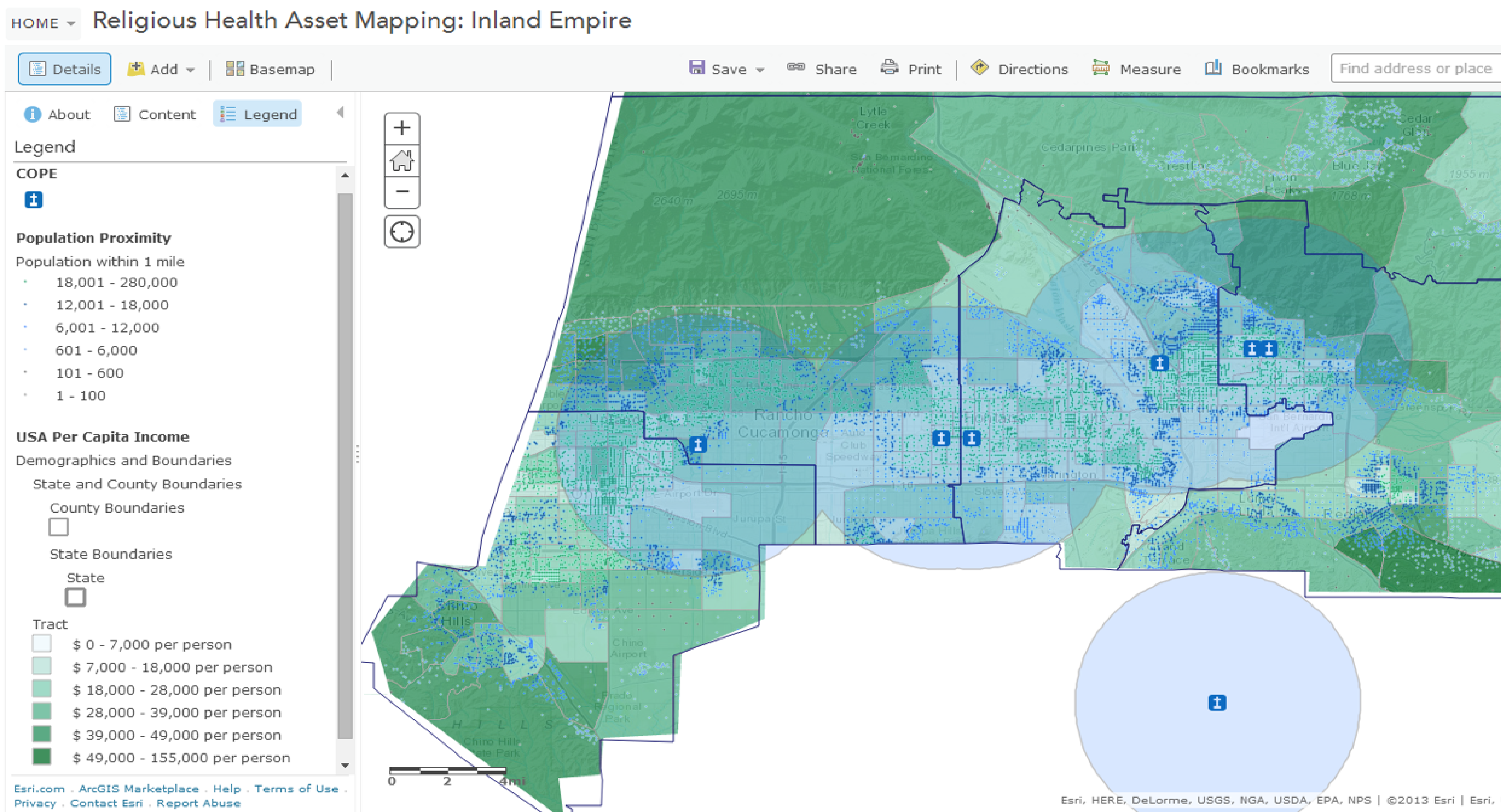

This lack of proximity to the church where they worship creates a significant challenge for a congregation to create effective ministry opportunities to it’s local community. As well, churches are notorious for creating wonderful outreach opportunities, but not really creating a collective impact model of outreach to the community where it resides. While random acts of kindness are important and life-giving, they do not necessarily move the dial on some of the social, health, educational, and economic disparities in a given region. We believe churches should be an integral and intentional part of the solution to these problems. However, in order to make this happen it is imperative to connect the congregation to the actual data on what is happening around their church (for Examples see Image 2 and 3- more generalized mapping of 7 different churches in the San Bernardino, Riverside Region).

In order to develop a plan to connect congregations to their local communities, it is imperative to use relevant and accessible data in order to get a clear picture of what is happening. A great resource for faith communities to find this data is the Community Health Needs Assessments that are done by not-for-profit hospitals in any given region. These CHNAs, as they are called, are mandatory for every NFP Hospital in the United States, and they must be accessible to the local community through the hospitals website. This will give a faith community the ability to see health disparity in their region.

Using this data, along with other publicly accessible data sources, the faith community can begin to see how their communities are taking shape, and begin to create interventions (ministries) that can address these particular needs. As well, they can look to partner with other organizations that might have a greater competency in some of these areas. This creates the church as a liaison to social resources, and perhaps places the church in a situation where it can be the hub of connection to what people in the community need.

To this end, LLUH and the Southeastern California Conference have decided to create this kind of model in a local church in the San Bernardino Region. The CrossWalk church has been around for almost 11 years, and has always been deeply missional minded. On that foundation, the church has agreed to become a model of health and wellness intervention for the community that surrounds the church. Given it’s location, a two-mile radius brings both the well-to-do, and the deeply underserved. The hope is that the church can become a hub of influence for the local community, but through strategic partnerships, strong collaborations, and innovative programs aimed at moving the dial on some of the social and health disparities. However, this does not neglect nor divert from the fact that this is first and foremost a worshipping Seventh-day Adventist community that can be deeply relevant to it’s particular geographic location.

GOAL: In a word, relevancy. However, this relevancy is not simply based on what we think the community needs, but based on data, technology, and ethnographic engagement with the local community. As well, the goal is to create a clear and intentional mission that becomes the identifying marker of the church in the community. All this being done within the theological framework of Adventist belief and values.

There is a question of whether or not this is a truly a prototype, or just a more intentional expression of what most churches do; and this is a fair question. Perhaps, the most unique attribute of this model is the bringing together of what Seventh-day Adventists have become known around the world for: health (health care), education, and ministry. The relevancy of all our work can be intentionally expressed to our local community, through our congregation, while making good use of the physical assets of the church facility. This is the goal, both for the growth of the congregation, the lifting up of the local community, and most importantly, for the Glory of Jesus Christ.

Dr. Gleason is an assistant professor in the School of Public Health and graduated from the School of Behavioral Health.

Typhoon Yolanda took over six thousand lives in 2013, and brought the world to stop for countless others. Countries around the world responded with food, shelter, aid and care. At home, beneath the bustle of San Bernardino, it takes much less than a typhoon to bring someone’s world crashing down. While we all endure our share of emotional bumps and bruises, research demonstrates that those who carry the weight of extra injuries will suffer for it, mentally, and physically to the tune of a twenty-year shorter life expectancy.

As a country struggles to find itself after a disaster, so does a person after a traumatic injury, be it mental or physical. A recently surveyed adolescent homeless community in San Bernardino reported 60 percent having high rates of trauma, and 40 percent with rates very high. Among these young people, nine out of 10 felt unloved by their parents, more than sixty percent had a family member go to prison, or have drug problems, or had watched their mother take abuse, and almost half had been touched inappropriately by an adult in their home.

The world has a plan to support the victims of Yolanda, sending provisions or emergency responders. What is our plan for responding to the needs of the thousands in our midst whose personal worlds have crashed?

The Loma Linda University School of Behavioral Health houses a team of international responders, specifically trained to work on an individual level with those suffering from the trauma of natural disasters. These short-term crises interventions are designed to be a quick and manageable way to restore a sense of control and empowerment by first teaching skills for understanding the body’s physiological response to stress, and second to provide tools for processing and releasing this stress.

Within San Bernardino are thousands who will benefit greatly from exposure to these aforementioned skills. The Loma Linda University School of Public Health has within her grasp the ability to put together her own team(s) of trained experts, going into community through churches, schools, clinics, business, or any other avenue to reach these suffering people.

Walking the streets around us are thousands of homeless, adolescents and elderly, witnessing all forms of dehumanizing aggression as they struggle to exist. We also have in our midst children who witness friends being shot in the street. Around the corner we have men and women returning to our community from war or prison, having seen things they cannot describe, struggling to fit in. Behind us there are young women who are treated like property instead of human beings.

Our neighbors have needs often difficult to see on the surface. Within the grasp of our school are the resources to bring empowerment and control, in the form of basic coping skills, to a people in high need of exactly that.

Flor Just graduated from the LLU School of Pharmacy in 2013 and is currently an inpatient pharmacist at Littleton Adventist Hospital in Colorado.

Pharmacists are fighting on the front lines against preventable diseases. With pharmacies at almost every corner, we are some of the most accessible medical professionals to the public. In fact, a 2013 Gallup poll on the most widely trusted professions, named pharmacists the second most trusted professionals in America.

With that trust comes a lot of responsibility. A responsibility to use our knowledge not only to heal the sick, but to also help prevent disease.

Throughout my time at Loma Linda University School of Pharmacy, I was able to use my knowledge to help promote wellness within my community. As a student, I was given opportunities to work with pharmacists in the San Bernardino area where I actively supported health and wellbeing. Thanks to a sponsorship from Walgreens, we were able to provide free flu shots to the underprivileged population of the city. In other instances, we were able to host free diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis screenings at various health fairs within San Bernardino County.

During pharmacy school, I worked as an intern at a Kaiser clinic in the heart of San Bernardino. It was there that I learned how important my career choice really was. Not only was I able to guide patients in selecting appropriate medications for their needs and how to properly take them, I was also able to educate them about the importance of preventing disease.

The role of a pharmacist in public health is ever changing. Pharmacists now routinely assess individual patients’ therapeutic needs, prevent adverse effects due to medications, manage chronic diseases, and monitor medication adherence. We now have opportunities to provide care to populations in areas critical to the mission of public health. This includes immunization programs, emergency preparedness and response, the prevention and control of infectious diseases, chronic diseases, and injuries. We are being taught in pharmacy school that disease prevention is key, and we are sharing that public health knowledge with our patients.

Thanks to the education I received at LLU SP, and the experience I was able to obtain by volunteering at various events in San Bernardino, I am now equipped with the knowledge I need to fight on the front lines of the war against preventable diseases.

Robert Perry is a 3rd year student at LLU School of Dentistry and a 2012 graduate of LLU School of Public Health. Robert works with the Foundation For Worldwide Health on projects locally and internationally, which includes overseeing five health clinics in the San Bernardino County.

What if I told you that one of the most communicable diseases known to man is also one of the most preventable diseases. Dental caries is one of the most communicable diseases in the world. In the United States 74% of persons 20-64 years old have dental caries (tooth decay or cavities), with 23.7% of them going untreated. It is not unlikely for untreated dental caries to transform into a systemic infection. Treating a systemic infection can lead to further health care costs or even death. Although this disease has an exceptionally high morbidity and incidence, it is often overlooked and undertreated. The incidence of dental caries could be lowered or even prevented with correct education and resources; a preventive measure that could lead to lower health care costs and a better standard of living.

Loma Linda University School of Dentistry and its students attempt to mitigate the burden of dental caries and those who suffer untreated almost daily. I am a part of a group of students who have established and sustained several free clinics with the mission of serving the under-served health care needs of residents living in San Bernardino and Riverside Counties.

One of our largest and most established clinics, located in Redlands, California, serves residents coming from as far as San Diego. When the clinic first started, it mainly served as a place for people to receive treatment when they had dental-related pain and could not afford to see a dentist. It was not uncommon for a patient to wait 3-6 months to be treated due to the high volume and need of the area. As the clinic grew and became more organized, we moved from seeing patients every couple weeks to twice a week. Currently, we serve around 650 patients each quarter and complete nearly 2,600 procedures totaling over $300,000.

As we began to see more patients each week, I was able to observe first hand the oral health status change of the region. The patient need at the Redlands clinic changed from urgent care to prevention; the dynamic of the clinic changed from patients coming in with pain to patients coming in for maintenance. The key to this success was educating the patients as we treated them. As we removed the decay and pain from their mouths, we would teach them how to prevent the disease that caused them so much pain. It is a true blessing to be part of a public health initiative that is proving successful to prevent disease, promote health, and prolong life among the population as a whole, but especially among our neighbors.

Laura graduated from LLU School of Nursing in 2014 and is working in labor and delivery at Redlands Community Hospital.

I find the subject of public health and health promotion to be a fascinating one. I was first introduced to the topic at the Center for Health Promotion, an extension of the Loma Linda University School of Public Health, where I was employed while attending the LLU School of Nursing to earn my bachelor’s degree. The idea of taking a local population, providing them with preventive care and regular health screenings, and helping them to maintain good health struck a chord with me. In the current political climate, the news is abuzz with the rising cost of health care, insurance issues, and availability of resources. From a purely fiscal standpoint, it is far less expensive to promote good health and maintain a generally healthy population than to treat a host of advanced medical issues and disease processes. Our local population and the nation’s populous as a whole are clearly in need of help in the fight for health. Through my education and employment, I have come to recognize the importance of public health in a world that seems to be steadily growing sicker.

During my penultimate quarter in nursing school, I was lucky enough to be assigned to a unique cohort in San Bernardino. Two other students and I were tasked with providing education to a group of pregnant and parenting teens at Cajon High School. For several weeks during the quarter we spent time with the students, listening to their questions and formulating ideas for presenting the information they sought. Using the students’ queries as a guide, we created three Power Point-based lectures on topics of interest to the class. Our material consisted of basic newborn physiological assessment, common infant/toddler milestones, safety and preventing illness, and parent-child bonding activities to promote healthy development. The three of us each presented a lecture and summarized the material in a game-show style quiz that the students thoroughly enjoyed. We were also able to bring in a guest speaker; the mother of one of the group member’s had been a teen parent and went on to become a successful nurse and business woman. It was extremely fulfilling to watch the students grow and learn over the weeks we spent together, and voice appreciation for the things we taught them. It is easy to forget the power of knowledge until you see it transform a life for the better.

I am currently employed at Redlands Community Hospital in Labor and Delivery. I feel privileged to work in an area that so heavily relies on education and health promotion. We see and treat women in many stages of pregnancy for a wide variety of obstetric issues. A key component of my work is education; teaching mothers of all ages how to maintain good health and support a growing life during and after pregnancy.

I cannot stress enough the importance of public health in San Bernardino and across the nation. I’m excited to contribute what I can to the cause, however small. If we all use our skills and passion for the benefit of the health of our communities, think of what we can accomplish!

Hans is a third-year medical student at LLU School of Medicine and is currently interested in pursuing internal medicine.

I’d like to tell you a story about a place called Pawnee, Indiana. It’s a quaint little place, and the centerpiece of Parks and Recreation, a comedic television show about a caricatured local government department in a fictional town. Pawnee is home of some great places to eat, but it’s also overrun with raccoons. Its citizens are pleasantly plump and delightfully belligerent at town hall meetings; indeed, its very motto is, “First in friendship, fourth in obesity.” Nearby is the town of Eagleton, a rich community that holds daily champagne brunches with Michael Buble and fills their pools with Evian water. The towns are often at odds with each other, with Pawnee resentful that Eagleton never seems to lend a helping hand.

Does any of this sound familiar? The relationship between San Bernardino and Loma Linda may not be as comically disparate, however, when one of the first chapels I attended as a medical student at LLU cited a statistic about how San Bernardino ranked as the fourth most obese county in the nation, my ears perked up. Public health by its very definition is an issue that concerns us, the public. Our neighbors on the other side of the freeway may not be overrun with raccoons, but they are certainly saturated with their own set of issues that should concern Loma Linda, a city so world-renowned for its health message.

As I enter my third year of medical school, in which I rotate through various specialties, I see the very important role that physicians play in being the bridge between private health care and public health. On one end, health care is indeed a very private issue that each patient deals with on a personal level; patients work with their doctors to achieve the level of health care that works best for them. On the other side, physicians are constantly keeping up to date on new medication standards, protocols, and cutting edge therapies and procedures that better the quality of life of their patient population.

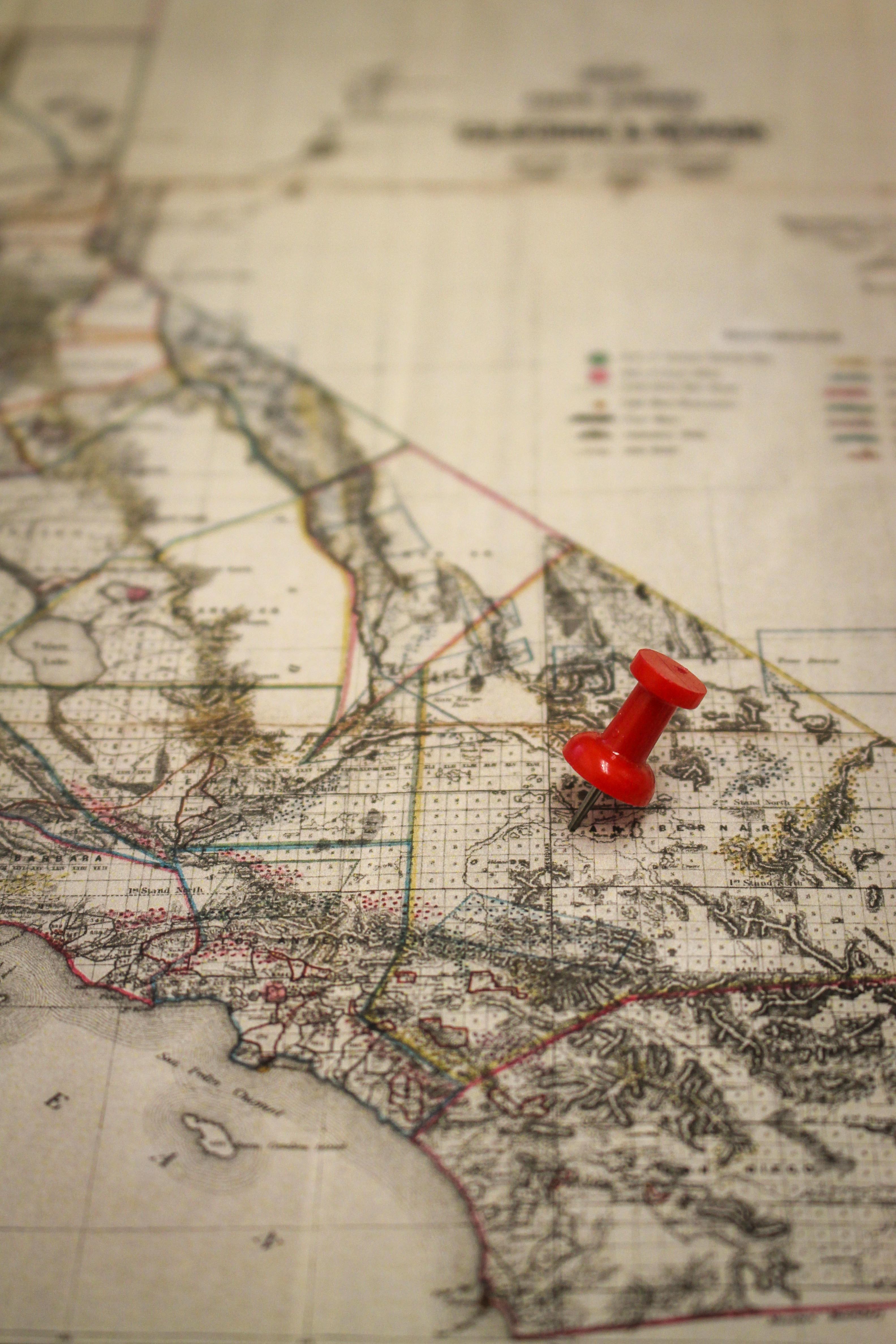

Building bridges has, indeed, always been the specialty of public health. Growing up, and to this day, I have always been a big geography nerd. One of my favorite stories is that of Dr. John Snow and the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. Dr. Snow plotted out the incidents of cholera in London during this particularly bad epidemic and noticed the cluster of cases centered on a particular water pump. In doing so, Dr. Snow essentially contributed to the creation of the field of epidemiology, a major component of public health. This bridge between geography, patient population, and health care absolutely fascinated me, and motivates me as a future health care professional to maintain the integrity of that bridge.

Which brings me back to the sister cities, Loma Linda and San Bernardino. The geography and proximity of our fair cities means that we cannot simply let a neighbor be ignored, especially when one of those cities has been deemed a geographic area where its residents live measurably longer lives; essentially, a paragon of health care. I understand that it isn’t as easy as proclaiming, “We need to help them!” Solutions must be proposed, cooperation must be encouraged, and bridges must be built. As a future physician, I recognize my vital role in those activities; I cannot be complacent about my patient population, which will come from far and wide. When health care professionals, city officials, and the citizens at large adopt that mindset, only then can we work toward a San Bernardino that is “First in friendship, AND in health!”